I have recently completed a performing edition of Ivor Gurney’s song cycle for baritone, string quartet and piano, The Western Playland (and of Sorrow) in readiness for a rare performance as part of the Finzi Friends’ Ludlow Weekend of English Song on 1 June.

In the autumn of 1919 Gurney attended a performance of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s monumental song cycle for tenor, string quartet and piano, On Wenlock Edge. Gurney was so fired up by this work, and the possibilities of the accompanying ensemble, that he immediately set to work on his own cycle for this combination, which, like the Vaughan Williams, set poems by A.E. Housman: Ludlow & Teme. The cycle was completed within a matter of weeks, and was brought to performance in a private recital in March 1920, sung by Steuart Wilson. So immediate was the success of this work that he was inspired to continue in a similar vein, and in May 1920 started work on a second Housman cycle, this time for baritone with string quartet and piano accompaniment: The Western Playland (and of Sorrow). In the writing of this Gurney returned to some previously written material, breathing new life and context into some of his songs originally conceived for piano. Where in Ludlow & Teme all except one of the seven songs had been composed anew (‘Ludlow Fair’ had been drafted the previous year for piano), four of the eight songs in The Western Playland were reworked from previous settings with piano. The new cycle for baritone received its first performance at the Royal College of Music in November 1920.

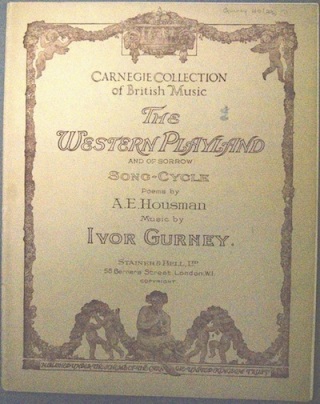

In the mid-1920s both of these song cycles were brought to publication by Stainer & Bell, under the auspices of the Carnegie Trust’s scheme for the publication of works by British Composers. Ludlow & Teme was submitted to the Trust in December 1920, offered the award of publication in May 1921 and was issued in print in October 1923; The Western Playland was submitted subsequently and was published by Stainer & Bell in February 1926.

The modern reception of these two cycles is quite different: Ludlow & Teme has come to be regarded as one of Gurney’s masterpieces. It is performed with relative frequency (helped by its being for the same voice as the Vaughan Williams – an obvious programme partner), and has in recent years been twice recorded (by James Gilchrist on Linn and Andrew Kennedy on Signum). In 2011 Stainer & Bell published a new critical edition of the work (edited by myself!) which incorporated a number of revisions to the work made by Gurney following its publication.

Where Ludlow & Teme is very much on the horizon of performers, promoters and record companies, The Western Playland is very rarely heard, and while it has been recorded some years ago, by Hyperion, it does not have the same presence in the musical canon as its predecessor.

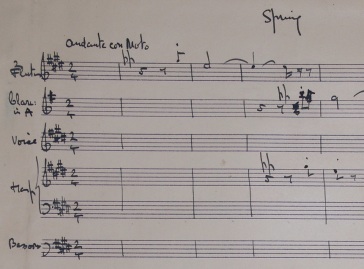

The reasons for this probably stem from the published score: there are numerous errors in the score which were not picked up when editing the work for publication, some of which make the work rather painful listening and, as a performer, one is left wondering how one deals with various ‘moments’. The reasons for this become evident when one is looking at the manuscript and published evidence that exists for the work. There is extant a set of manuscript piano (vocal) scores for the cycle, a manuscript full score, the published full score and parts, the published vocal score, and, in the Gurney archive, a copy of the published vocal score with some small corrections and amendments made by Gurney in 1926. When editing the work and seeking to rectify the numerous errors (what are obviously errors and not Gurney’s idiosyncrasies) one might think that all of this source material will help clarify matters; but no: the manuscript scores and the published scores are almost entirely different. One might even go as far as saying that they might almost qualify as a new work! There are passages that are similar, with some revisions, but other parts are unrecognisable. Furthermore, one might imagine that the vocal score might be a precise reduction/reflection of the full score. This is not the case: there are numerous departures, and it is evident that they were written and perhaps conceived independently. What is particularly interesting about the manuscript material is that it is evident that the manuscript full score was that score submitted to the Carnegie Trust. It was therefore this work about which the Trustees wrote, in their report recommending publication, ‘The melodies, sensitive and poetic, are admirably suited to the lyric quality of the verse, covering a wide range of emotional expression.’

When it came to submitting the score for the final act of publication, in 1924, Gurney made a wholesale revision of the work. Textures were added and reworked, the scoring often wholly altered (one song originally scored largely for strings was in revision accompanied largely by piano); harmonies became more diffuse, in Gurney’s impressionistic vein; and the songs in parts substantially redrafted. Given that the work had already been studied and approved for publication, one wonders whether there was any editorial eye cast over the score when it came to publication. The publisher, one suspects, might have thought that any interference between approval and publication would amount only to some small corrections or slight revision. A wholesale rewrite would certainly not have been expected. Indeed, one might go as far as to ask whether the work would have been awarded publication had it been first submitted in the revised form.

While I opened by saying that I had edited the work for performance, what I have undertaken thus far has merely scratched the surface. Because versions of the score are largely irreconcilable, I have sought to clarify problematic moments with reference to the published vocal score and the extant manuscript material, making some small amendments to the lines – in line with the other material (what could be errors, misreadings, or just amendments in the texture that Gurney didn’t think through), and in one instance correcting a terrible moment which I am certain arose from the use of a wrong clef. One of the songs was problematic to the extent that I took the rash decision to return wholly to the original 1920 version, which was much more coherent. The ethics of this decision are very difficult, and it is a grave inconsistency. However, I think that in the short term the performance will be the better for it, until I can spend more time than I have had in order to work through the songs. This decision has scratched the surface of an underlying thought that has arisen during the process of editing the score: that rather than trying to reconcile the scores, one should edit the original version as a whole and put this out into the world as a valid version of the cycle which I think might speak with greater clarity and hopefully allow these wonderful songs to be appreciated more readily. The sometimes overworked textures of the pre-publication revision, and some of its diffusing of harmonies, however, do create some real magic in the work, and so one doesn’t wish to lose these. It is, I think, going to be a case of bringing long thought editions of both versions to performance so that we can make comparison in performance. Only then, I think, can we truly assess the parallel versions of the work. A performance/recording also needs to be undertaken in the piano version, which bears great validity as an independent work.

As far as the post-publication revisions to the vocal score are concerned, these add occasional additional notes/lines to the piano texture, which work in the piano version; and some tempo markings at the end of the cycle help in clarifying the work’s extended instrumental coda (I have added these tempo markings into the full score). A curious tirade of additional flats are something that I have questioned, whether it is successful or not, but this seems to have been something Gurney added, it would seems, to a proof of his 1924 version, and which the publisher removed or ignored. In a letter of late April 1925 Gurney asks Marion Scott, lamentingly, ‘why did they take those flats out in “The Aspens”?’. One can only presume that the additions to the published vocal score are Gurney’s attempt to reinstate what the publisher removed.

In spite of all of these textual difficulties, The Western Playland is a remarkable and worthwhile work of some great beauty. ‘Loveliest of Trees’ and ‘The Far Country’ both rival George Butterworth’s fine settings, and more besides. So if you happen to be in or near Ludlow on 1 June, book now to hear Jonathan McGovern, the Carducci Quartet and Susie Allan give a rare performance of this work that deserves to be so much better known. I’ll see you there!