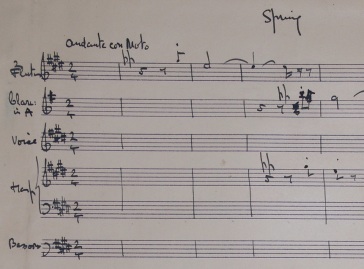

In early 2012 I gave Adrian Partington a tour of the Ivor Gurney archive. One of the items I showed him was the manuscript full score of ‘Spring’ from Ivor Gurney’s Five Elizabethan Songs – a set of songs that includes Gurney’s most popular work, a setting of John Fletcher’s ‘Sleep’. Some time after this meeting I was asked whether I should like to reconstruct the remainder of the full score of the ‘Elizas’ (as Gurney called them), and to perform them during the 2013 Three Choirs Festival. The answer was obvious (Yes!), and, given that the songs were written in December 1913 and the centenary of that writing is therefore close upon us, particularly timely.

Gurney’s ‘Elizas’ are his first acknowledged masterpiece, and their quality was acknowledged by Gurney himself in a letter to his friend and fellow Gloucestershire poet Will Harvey, in which he asked ‘How did such an undigested clod as I make them?’ I am sure that any who know the songs will be thinking, ‘What does he mean, “full score”? Why should they need reconstructing?!’ It is not widely known that Gurney originally intended these songs to be accompanied by the rather curious ensemble of two flutes, two clarinets, two bassoons and harp – a curious ensemble indeed! Only one of the songs is extant in full score, and a few of the manuscript piano scores bear some indications of that scoring, so the task ahead is to take these indications as the starting point for the reimagination of those scores.

It is probable that the scored version of the songs was performed only once, in an orchestral concert at the Royal College of Music. The fact that this performance took place during a full orchestral concert made their programming rather straightforward. The necessary instruments could come forward from the orchestra and then return to their stations for the remainder of the programme. Such was not my luxury when trying to programme the forthcoming Three Choirs Festival recital, for which the only forces available are those specified by Gurney. Furthermore, it was asked that this be a ‘Gurney and Friends’ programme; so what works from those composers in Gurney’s circle could one draw upon to create a 70 minute recital programme when the instruments available to you are voice, 2 flutes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons and a harp. There are not many works that spring immediately to mind, but nothing is impossible!

It is probable that the scored version of the songs was performed only once, in an orchestral concert at the Royal College of Music. The fact that this performance took place during a full orchestral concert made their programming rather straightforward. The necessary instruments could come forward from the orchestra and then return to their stations for the remainder of the programme. Such was not my luxury when trying to programme the forthcoming Three Choirs Festival recital, for which the only forces available are those specified by Gurney. Furthermore, it was asked that this be a ‘Gurney and Friends’ programme; so what works from those composers in Gurney’s circle could one draw upon to create a 70 minute recital programme when the instruments available to you are voice, 2 flutes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons and a harp. There are not many works that spring immediately to mind, but nothing is impossible!

SO: The first task was to make a list of composers who had connections with Gurney, identifying those whose work it is almost essential to include and those whom it would be good to do so. In honesty, with the right forces, one could have created a recital of twice the length or more, if one had the option of a piano to hand. There were so many that one should have liked to have included, most of whom it was impossible to do so with the forces to hand: Arthur Bliss, Arthur Benjamin, Rupert Erlebach and Francis Warren were a few of those whom I should have liked to have represented and whose work I explored. In the end it boiled down to a few essentials:

- Gurney himself;

- Gurney’s teachers: Charles Stanford & Ralph Vaughan Williams;

- two RCM staff who were hugely influential: Hubert Parry, the Director of the RCM and another local ‘Gloucesterian’, and, most importantly, Marion Scott;

- his close boyhood friend, Herbert Howells;

- a composer whom Gurney never met, but one who was influenced by Gurney and, notably, did more than anyone else before 1978 to promote his music: Gerald Finzi.

But how might these work with the available ensemble? There are few works by any of these that are scored for combinations of these instruments. Howells wrote a Prelude for harp (‘Prelude no.1’, although no further preludes were written), which must obviously form a part of the recital; and Vaughan Williams’s Household Music, which can be performed on any combination of four instruments of the correct registers, was long in the running, in whole or in part, but was ultimately omitted owing to time constraints and the cost of hiring parts, which would have been necessary but problematical. Such flexibility of instrumentation was something that would have to be brought to other works. One could have sought songs that would work on harp in lieu of the piano – which I have done to some small extent – but I also had to start thinking, as the cliché goes, ‘outside the box’.

For instance, Marion Scott – whose musical works are very rarely heard and whose importance for Gurney lies in the fact that she looked after all of his business affairs, during the war and after – composed a Romance for oboe and harp. The presence of the harp makes this a must, so a compromise must be made and the work passed to the clarinet. The manuscript for this arrived yesterday, so I am looking forward to playing it through in the next couple of days. (The lack of an oboe in the ensemble also discounted some wonderful potential works that I had on my list, such as Vaughan Williams’s Ten Blake Songs.) More creatively, the potential for more involved arrangement is great, and allowed the choice of a programme that I hope will cast new light on the works in the programme. Some works were long considered (Vaughan Williams Four Last Songs – how wonderful ‘Procris’ would be arranged with perhaps flute, clarinet and harp – and indeed the others!). However, I think I have put together a particularly interesting programme, bringing together both personal relationships and musical influences.

For instance, I have been able to choose two Shakespeare settings by Hubert Parry, which are – to my ears – blatant precursors to Gurney’s Elizabethan Songs: ‘Blow, blow thou winter wind’, which musically pre-echoes Gurney’s ‘Orpheus’, and ‘When icicles hang’, which, with its bird calls, is a very distinct precursor to Gurney’s ‘Spring’.

One of the difficulties of presenting a novel form of a work and being constrained to that same ensemble is that one is at risk of pre-empting the moment of originality. And so while I hoped to make the arrival of the Elizabethans in the programme a real moment of arrival rather than an ‘Oh, its this ensemble again, which we’ve already heard in the other works’. It needs to seem like a culmination: the previous works must prepare the way, but somehow they mustn’t steal the thunder of the main work. This is a very difficult thing to achieve, and in fact had to be compromised in the context of the programme and balancing the demands on each player and some of the musical relationships I wished to portray; so I must hope that its thunder will not be stolen nor its effect lost in the preceding works — although if I exchange one of the Howells pieces in the second half with the Stanford in the first……. Still the programme writhes in my mind! I must lay it to rest.

The Five Elizabethan Songs closes the first half, which left the question as to the work which might close the programme. There was one work that seemed an obvious counterpart to the Elizas, which would balance the programme nicely: Gerald Finzi’s set of five Shakespeare songs, dedicated to Vaughan Williams on his 70th birthday: Let us Garlands Bring. Gurney’s work had a great influence on Finzi, who heard Gurney’s genius in his first hearing of ‘Sleep’, in 1920. It is my belief that Let us Garlands Bring is directly descended from the Elizas and is in some ways a homage to Gurney’s set. So: I have sought and be granted permission from both the Finzi Trust and Boosey & Hawkes to arrange the work for the same ensemble as the Five Elizabethan Songs, for a single performance at the Three Choirs Festival. I am enormously grateful to both Trust and publisher for allowing me to undertake this task, which I hope will affirm the link between these two works and shed some new light on the Finzi.

And so, the programme is settled; the accompanying ensemble is nearly gathered (I hope they’ll like the programme and that few, if any changes will be necessary); and I am extremely pleased that mezzo-soprano Susanna Spicer has recently agreed to appear alongside me in the recital. Susanna will most notably be singing the Elizabethan Songs, which were intended by Gurney to be sung by a mezzo, and her joining the ensemble allows scope for a couple of duets – one composed thus, and one not! All that will remain is for you to come along to the recital on 29 July 2013 to hear for yourself how it all works out. It should be a unique and interesting experience on many fronts. To find out more, visit the Three Choirs Festival website. I hope that the full programme list will be up there before long to entice you further – should you need it!

One of my day (or rather, more often evening-) jobs, with which I attempt to keep the ‘wolf from the door’, is propping up the choir stalls in Lichfield Cathedral, serving as Bass Lay Vicar Choral – a sometimes curious choice of occupation for an ‘atheist’ (in some sense. How long have you got?!). I have sung in church/cathedral choirs since the age of seven – so, allowing for a couple of short breaks, that makes about 25 years – during which time one cannot help but develop a favourite tune amongst the hymnody.

One of my day (or rather, more often evening-) jobs, with which I attempt to keep the ‘wolf from the door’, is propping up the choir stalls in Lichfield Cathedral, serving as Bass Lay Vicar Choral – a sometimes curious choice of occupation for an ‘atheist’ (in some sense. How long have you got?!). I have sung in church/cathedral choirs since the age of seven – so, allowing for a couple of short breaks, that makes about 25 years – during which time one cannot help but develop a favourite tune amongst the hymnody.